Sydney Festival Turns Forty

Lifting the curtain on Sydney Festival. Commissioned by the City of Sydney to interview past and present Directors of Sydney Festival, Martin Portus reflects upon the evolving nature of Sydney Festival and the important role the directors have played.

Martin Portus is a critic, arts journalist and former broadcaster. This is an edited version of a speech Martin Portus delivered in the week of the Festival’s 40th anniversary program launch in October 2015, having just completed the oral history project.

Sydney Festival through the eyes of its directors: 1977–2016, commissioned and published by the City of Sydney, contains the personal recollections of all living Sydney Festival artistic directors. Behind the scenes anecdotes and never before heard tales of some of Sydney’s most memorable stage performances are available online.

Sydney Festival, compared to other festivals, has always relied heavily on its sponsors and donors. They’ve been significant in evolving the intrinsically Sydney character of this weird summertime, popular arts event.

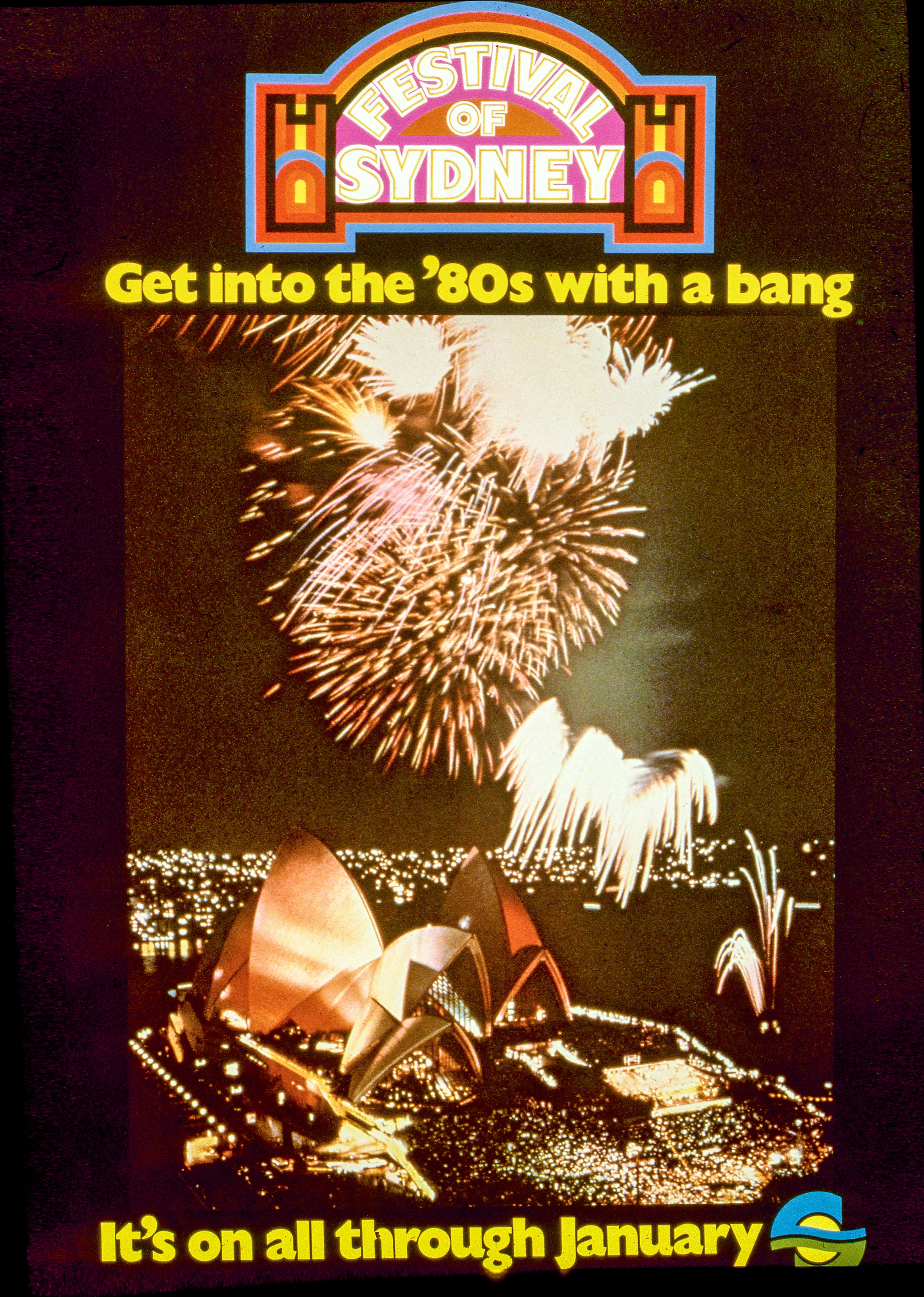

Hence its first name, the Festival of Sydney.

Forty years on, world-wide, no other sports such a profusion of outdoor spectacle and mass free events and concerts. None quite gets that mix of high and low art, a summertime frolic in thongs mixed with dressing up for top international arts, and now spreading from the Harbour across western Sydney. It covers and mashes up all the art forms, and juggles the serious and confronting with a crazy new year optimism conjured up by those ferrythons and fireworks.

This festival wouldn’t have that distinctive character if its directors – and I’ve done long interviews with six of them – had somehow achieved the level of government funding they often dreamt of, hoping to match those better-funded, interstate festivals.

The Festival’s driving need for sponsors and to build artistic and commercial collaborations across the city has, arguably, made it so oddly expressive of Sydney.

Stephen Hall was a master of this cobbling together of opportunities. Across from the Town Hall where it started in 1977 – initially with the big bang of New Year’s Eve – in his Festival office amongst the rats in the unrestored QVB, Hall boasted that his door was always open to any new idea.

Frankly, those early programs looked like it – like shopping catalogues they were, full of ads and a 70s mishmash of community events, smiling ethnic faces in costumes, face-painting and clowns, heaps of sporting highlights and pages of umbrella events pulling in every available local act. No wonder the story went that this new festival was just to bring shoppers back to the city in January – certainly retailers then were prominent on the board.

But it was the start of an arts festival, and certainly more sophisticated than the springtime Waratah Festival and Parade which it replaced. Melbourne’s Moomba, eat your heart out!

Ten years on, Kerry Packer certainly liked it that way. On the eve of one Sydney Festival, Hall was suddenly down $250k when a sponsor pulled out. He’d heard Kerry could be persuaded to step in but the summary argument should fill no more than one page. Hall battled for brevity (which would have been welcome in his brochures!) but achieved his one pager. And, he says, Kerry was mightily impressed. He gave Hall triple the amount, $750k, and when Stephen asked cautiously for how long that might last… As far as I’m concerned, in f**king perpetuity, was the answer. In fact, it lasted 23 years.

Kerry said that he liked, from his ACP office, seeing the kids all playing below at the Hyde Park events – and he added, seeing their parents spending money in town. He was less enamored of the arts bits. *

And so Sydney’s long tug of war continued for what was at the heart of the festival: was it the arts or its popular, mostly outdoor events? The battle was to climax when Anthony Steel took over in 1995.

It was fashionable for people like me, then a Fairfax arts journalist, and indeed for Hall’s two successors, to disparage his arts legacy, to sniff that compared to others, his festivals lacked arts rigour and focus. A mixed grill, Leo called it.

Maybe, but Festival Hall, as they dubbed him, created so many of its now foundation events – that festival village in Hyde Park, the Coca Cola Bottlers 1940‘s Dance Hall, his programs of Australian dance and new theatre and, yes, the Ferrython and those free Domain concerts with their staggering attendances.

And buried in his wordy programs were often impressive, edgy international acts. He started what became a parade of Irish theatre and gave us our first experience of a foreign language company, back in 1981. And later, Spain’s mad La Fura del Baus at the Showground, running through the audience with offal and chainsaws.

Stephen Hall died last December. The National Library of Australia holds interviews with him conducted just a month earlier. The Sydney City Council website now features my interviews with the six directors who followed.

With his Oxbridge manners and impeccable festival credentials, honed first in Adelaide, Anthony Steel was something different. “The only brief I ever had was Keep It Popular,” he remembers. “It made my heart sink but I understood why.”

Steel wanted the Domain concerts – which swallowed an eighth of his modest budget – dropped from the main program. Key sponsors didn’t like that; nor did they like his risque poster design – it might scare away the Mums and Dads.

Steel was more successful unravelling the festival from Carnivale, whose often folksy ethnic events had been entangled with the festival for a few years. The Sydney Writers Festival was soon after let free from the umbrella.

While he ruffled multicultural feathers at home, Steel raised the bar in quality international acts expressive of diverse world cultures. Dancers from Brazil, gyspy music from Rajasthan to the Nile, the Gumboot Dancers from Soweto, and Philippe Decoufle’s acrobatic dance to open the gloriously restored Capitol Theatre.

But his lasting legacy were the free spectacles outdoors on the forecourt of the Sydney Opera House – like Barcelona’s firey Els Comediants or that mighty sendup send-up of Hollywood epics from France’s Royal de Luxe. And Steel brought visual artists and their installations out onto the streets, most notably with Jeff Koons’ enormous Puppy outside the MCA (with thanks to John Kaldor). Steel was an artistic adventurer.

A water theme trickled through his last festival with arts happenings in pools and bays around the Harbour. French sound artist Michel Redolfi, for example, beamed his Sonic Waters underwater at Nielson Park. Steel remembers “quite a few rather surprised Greek families having their picnics whilst we were all in our bathers, sticking our heads underwater to hear Michel’s gurgles. Great fun but serious, serious musical accomplishment as well.”

Steel hoped for a fourth festival to perfect his Sydney formula, but it was not to be. Premier Bob Carr – and also then the Festival’s President – was too impressed with Leo Schofield’s success running the Melbourne Festival, to say nothing of his capacity to raise cash.

Schofield doubled the number of sponsors for the 1998 festival and had a budget of more than $10 million to play with, almost $4 million more than Steel’s before.

Schofield further tightened the Festival’s program and promoted key hero works. Curiously, these were usually operas, ones rarely performed and preferably Baroque. Our marketing man made festival hits out of Handel, Richard Strauss and something Mozart wrote when he was 14.

He did however loose a fortune on Monteverdi’s The Return of Ulysses at the new Lyric Theatre – in the casino just past beyond the one-armed bandits. But that didn’t stop him going to Bob Carr the next year for a one-off $1million to stage Electra. He got the cash and, luckily, that was a box office winner.

Classical music was back on the program and popular traditions in flamenco, Irish and physical theatre were now established. Schofield also staged some significant Australian theatre – notably Cloudstreet – but he rejects that festivals should invest in local artists and productions. Festivals, he says, should showcase the best, not be defacto funding bodies.

It’s a reminder that Schofield comes not from the arts profession but instead identifies as “a totally Grade A Professional as a member of audiences.” You can see why he insisted on writing every word in his hugely oversized festival brochures.

“I remember,” he adds, “Anthony Steel rather disparagingly, I thought, said that one of my festivals had ‘high-brow, low-brow, middle-brow, no-brow’. Well, I don’t have a problem with that at all. I mean it’s called an audience, isn’t it?”

At one time Schofield was director of four Sydney Festivals, chair of the SSO, a newspaper columnist and director of both the Olympic and Paralympic arts festivals. No wonder they called him Mr Sydney.

For the boyish Brett Sheehy, he was a tough act to follow. But Sheehy had served a six year Festival apprenticeship. He’d been Steel’s bean counter and was deputy to Schofield through endless sponsor meetings. And at 42, he was part of a generational change happening in the new century across many Australian festivals.

For his first, 2002 festival, Sheehy defied Sydney’s post-Olympic hangover and matched Leo’s $4 million in sponsorships. And he brought to the festival a new younger demographic. Ticket prices were reduced, more theatre, dance and hybrid arts appeared, and in place of the “rarely performed opera”, Sheehy turned to Theatre du Soleil.

In Paris he persuaded Ariane Mnouchkine to bring her 85 artists to stage the Flood Drummers at the old Royal Hall of Industries. An unconventional new venue and an immersive epic, flooded with water, and with a world music dance party in a nearby pavilion – it helped rebrand the festival for younger Sydney.

He also took the free opening night spectacle to new crowds at Sydney Olympic Park. Circular Quay was now just too small. Sheehy’s first programming in Parramatta began the Festival’s now significant push to the west. He pioneered staging classic films with live music and, in a harbinger of the Vivid Festival to come, began illuminating key Sydney buildings.

Sheehy also built broad programs around significant artists like David Byrne, Leonard Cohen and Samuel Beckett. Talking Culture forums were a priority. So too was the commissioning of new Australian theatre, opera and dance, including the first of key festival works from Kate Champion.

Importantly, he didn’t fiddle with the Ferrython, or meddle with the Domain concerts and the traditional 1812 Overture! Polling in 2003 by the Sydney Chamber of Commerce showed Sydneysiders judged the Festival as the city’s most popular city event.

Brett’s contract was extended to do 2005; he was poached anyway to do the next two Adelaide festivals, and later Melbourne’s. His only regret was missing out on Premier Carr’s last cheque. As Carr left office soon after the 2005 festival, as one of his last acts he signed a cheque which, finally, near doubled the State’s historically modest input.

It was gold for Fergus Linehan. Coming from running the Dublin Festival, it was six times his usual budget. Linehan was also amazed at the heavyweight power of the board which then included the Premier and the Lord Mayor (then Lucy Turnbull) or their representatives, top public servants who could make things happen.

He was also awed by the crowds drawn to the Domain. And transfixed by the beauty of the surrounding Harbour. “We’re just going to get upstaged by this all the time”, he thought. “It’s like always walking around with a ridiculously good looking person.”

But he found the festival didn’t pass the Taxi Test, when he told drivers where he was working.

“They’d go ‘What’s that?’. Or they’d say ‘What’s that, and doesn’t Leo Schofield run that?’.”

By Linehan’s third in 2008, which launched the massive free Festival First Night party across the CBD, the taxi test was well passed. The best way to get mass attention in this town, he concluded, is to have road closures.

Linehan’s greatest genius was identifying both niche and big star music acts to match the broad tastes of a new digital generation, now connected to the tunes of their grandparents as instantly as to those of their peers. And with income from touring now replacing recording sales, these diverse artists flocked to Sydney.

Still, after that peak in 2008, he and the Festival were questioning whether this could last. Could a now celebrity-led, mainstream, high budget festival still play a sustainable arts role promoting the unpredictable, the provocative and the local?

Then the Global Financial Crisis pulled out the rug.

Lindy Hume was the first woman to direct Sydney Festival. She’s alive to the mischievous coincidence that the post-GFC festivals (her first program budget was cut by $1 million) went to the girl

As an international opera director, Hume was also the first artist in the job. This she says meant she could visit and contribute to rehearsals without artists thinking, “the suits had arrived”. And developing new, connecting, perhaps darker stories about and for her hometown of Sydney was her driving narrative. Black Capital in Redfern stands out and the work of Wesley Enoch; he takes up the reins soon as director of the 2017 Festival. So too does her mass staging of Indian megastar A H Rahman and his Bollywood spectacular in Parramatta Park.

Along with 43 Rajasthani musicians in The Managaniyar Seduction, this became urgently needed soft diplomacy after those widely reported attacks on Indian students. Hume incidentally was also the first director to be ferociously vilified for a couple of shows which flopped. Probably didn’t help she’s a girl.

Belgium’s Lieven Bertels is our first European director from a non-English speaking background. Compared to programming the established Holland Festival, he was totally converted by the model of Sydney’s in summer mode. He loved its “very dynamic mix between high and low art … that isn’t about a hierarchical ladder … and has all these forms of expression, cultural expression shoulder-to-shoulder.”

Bertels sees himself as a hands-on director interested in all aspects of festival-making, a bit of a Belgium boy scout, a Tintin. No doubt this helped him survive the axing of Festival First Night, which Bertels replaced with the popular – and far more sustainable – expansion of Hyde Park into a full Festival Village. Between the trees, the ghost of “Festival Hall” could here take a small bow.

And with a nod too to Leo, Bertels turned to operas and classical music but here mashed in astonishing hybrids and settings. Semele Walk dressed up Handel in the outrageous costumes of Vivienne Westwood. Those chainsaw-wielding boys in La Fura del Baus were back, this time producing a new-look Verdi opera. And in 2014, part underwater, was Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. The critics couldn’t quite decide, but this baroque opera is the highest earning single show in Sydney Festival’s history.

Meanwhile, the King of Belgium made Lieven a Knight of the Order of the Crown.

And when I ask him about the increasing competition faced by the Sydney Festival, from venues now keen to join in on January, from ever new festivals and events crowding out the Sydney calendar and interstate, he’s relaxed.

Festivals are flexible enough, he says, to be at the avant garde. They are able to take the lead and thrust together new arts experiences, to discover new spaces and to grab new audiences. It’s no wonder that so many imitators and collaborators, so much arts-making industry, tourism, commerce and sheer summertime exhilaration has followed in the wake of the Sydney Festival, after now forty years.

* The author acknowledges the National Library of Australia for providing access to ORAL TRC6667 – Stephen Hall interviewed by Margaret Leask.